Music Theory: Actualities vs. Possibilities

“What is musical reality? What is a musical actuality?” I’ve come to ask myself these questions in light of student concerns, interests and presentations specifically stemming from this year’s Pedagogy of Theory class.

Theory itself is too abstract, non-relevant—the primary concern is that which will achieve immediate results in classroom and lesson settings, with Performance ultimately the main locus focus of attention. Indeed, we, as the members of the Theory Department, say in our collective syllabi…

“Coursework should be thought of as not only classroom activity, but also as small-scale, highly-focused versions of musical reality.”

In all honesty, this is meant to encourage students to prepare solfege and part-writing homework with the utmost attention to detail and musicality. Thoughts of similar ilk seem to be an over-riding concern among those who teach theory these days: not Theory itself, but rather its practical application. If preparing homework is akin to preparing for a lesson or a performance, is that an end in its own right?

This is a minor third, and you play/sing/hear it this way. This is an eighth-note, and you feel it this way. These types of approaches are undoubtedly well-intentioned but ultimately self-defeating, opening several different cans-of-worms. Will performances and hearings of these things be the same in all contexts and styles on all instruments and voices?

This train of thought is actually contrary to historical evidence (which mostly suggests the reverse…) and perhaps may ultimately harm music by stunting creativity from within the field… (has it already?)

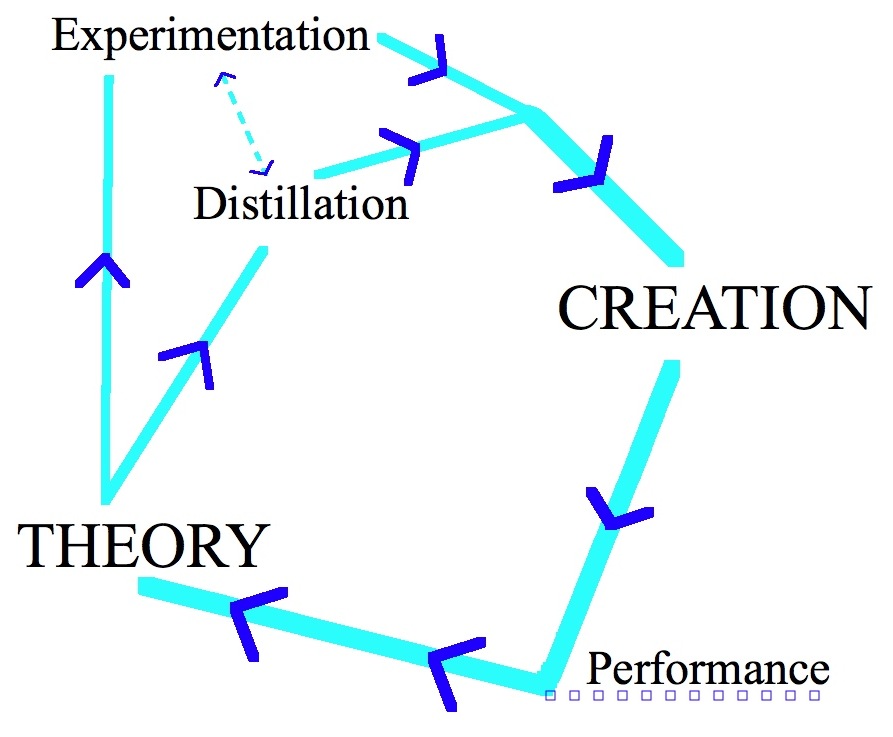

I suggest that folks are too performance-biased, unwilling slaves to the literature—RE-creationists! Is that actually a useful result? There are useful aspects of that kind of thinking, but performance cannot be THE result, instead is has to be the beginning! The equation needs to be revisited, or re-calibrated so that Performance rather marks the entry point of the Theory cycle…

…ultimately raising and addressing the following questions:

What was that? Did that work? How did it work? Why did it work? Is it duplicable? Is it comparable? Is there a model? Has is developed from some previous form? Can I make it work in the same way? Can I improve upon that? Can I further develop that? WHAT’S NEXT?!?!

Theory is not solely preparation for musical actualities, but also it is there to introduce and explore musical possibilities! Not just re-creation, because then the art form is dead, but rather….

Distillation/Reduction:

- Guido d’Arezzo — compose with only one pitch per vowel

- J.J. Fux — think/hear/teach in whole-note species

- J.S. Bach Chorales — quarter-note reductions of harmonic-phrase units

- Heinrich Scheker — think/hear/teach with unending variations and prolongations of cadential templates

- Nicholas Slonimsky — propose over 1,000 new kinds of scales

Note that thes above list includes methods and techniques that are often SEVERAL SCALES OF MAGNIFICATION REMOVED FROM MUSICAL ACTUALITIES MANY OF WHICH HAVE BEEN RIGOROUSLY TESTED VIA

Experimentation—Assumptions that get tested, Questions that get asked:

- How far can you stretch a minor third? On a piano, clarinet, or natural horn? In the blues? As the combination of two sine tones?

- How far can you push and pull an eighth-note? In the style of Bach or Wagner? In Dixieland, Sing, Bop or Funk? In different tempos? As a discrete unit of time? As a pulsation of Acoustic Beats?

COMPOSITIONS that push forward instead of regurgitating.

PERFORMANCES that address issues or ask questions.

IMPROVISATIONS that allow real-time explorations.

ANALYSES that inspire better listening/hearing/imagining.

TEACHING that explains actualities, yet opens the door for further possibilities…

Evidence suggests that teaching is one of the most important things that separates humans from apes, the ability to deliberately (not just imitatively) pass on a skill. Beyond that basic definition, “part of teaching is being able to coordinate your attention with another person’s attention” and that, I think, is also a pretty fair definition of music. The highest aim of any art is to express & share a viewpoint, that is… to teach!

All in all, the point of Theory is to not to restrict one goal’s along a unidirectional path, but rather to provide students the means to traverse the self-aware feedback loop that is MUSIC.